By Gideon Levy.

Late last month, as night fell on the new temporary quarters sheltering 37 Bedouin families of the Kaabneh tribe who had been rendered homeless overnight, some slept under the open sky. Others crowded into two tents they had hastily erected on land provided as a short-term refuge by generous Palestinians from a nearby village.

Most of their property had been left in their village, to which they feared to return. Israeli settlers had rushed in to forcibly appropriate its lands, use their fields for grazing, and prevent their return – even clearing away some of their furniture.

The previous night, these families had been sleeping in Ein Samia, their village, a few kilometres from their new temporary shelter. Ein Samia had been their home for more than four decades, until the approximately 200 residents were forced out overnight on 21 May.

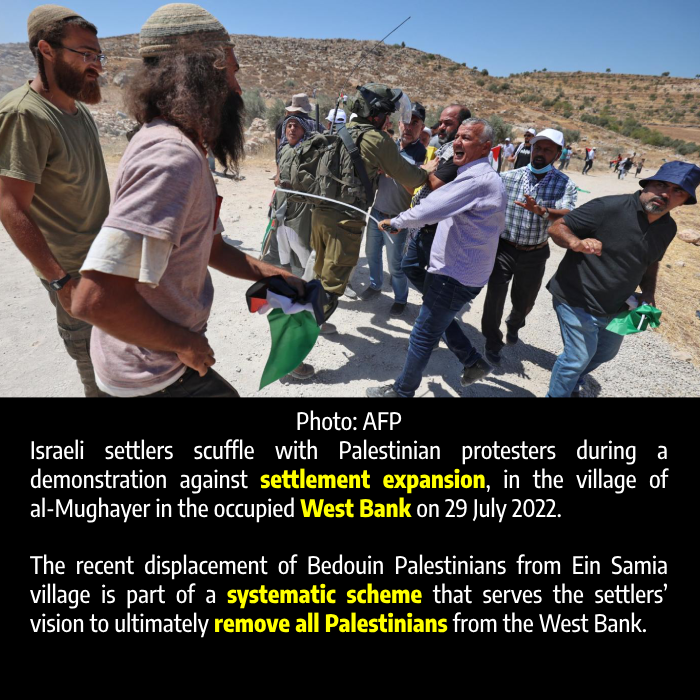

This displacement, spurred by violent settler abuse, is not an isolated incident. It is the “silent transfer” model in all its ugliness: a systematic scheme that serves the settlers’ vision to ultimately remove all Palestinians from the occupied West Bank.

The settlers’ success in Ein Samia, and before that in another nearby shepherding community, will encourage them to continue along their chosen path. They have already managed a partial ethnic cleansing of areas of the Jordan Valley and southern Mount Hebron.

From the Bedouin and Palestinian standpoint, Ein Samia is unequivocal proof that the Nakba, the Palestinian national catastrophe that accompanied Israel’s founding in 1948, is still not over. It has continued mostly without interruption since then; the catastrophe has not ended.

Israel continues using the same methods with the same national goals. The ultimate intention has been revealed as a state for all Jews – and for Jews only, from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. Ein Samia is the model for what some term the second Palestinian Nakba. Only the international community can prevent this from happening.

A few days after the evacuation of Ein Samia, I visited the abandoned village and the temporary refuge of the Kaabneh families. At the village left behind, from underneath some damaged plywood came a faint bleating noise.

Lifting the board revealed a heartbreaking sight: six tiny puppies lay in a heap, holding on to one another – frightened, sad, weak and thirsty. Evidently, their mother departed with the villagers, leaving the pups to their fate in the desert. The sight was heart-rending, and how would we save them?

The helpless puppies were not the only difficult sight in Ein Samia. Where once a Bedouin community of shepherds lived, now there was nothing but the scant remains of their village on the arid land. That they fled quickly, in a panic, was evident.

Meanwhile, a settler with long side curls who was already grazing other animals on the abandoned fields of Ein Samia turned to us, muttering what sounded like threats. The smell of sheep lingered. Around the area we saw tables, armchairs, rugs, sofas, a wardrobe with its drawers pulled out, children’s board games and a model BMW car.

There was a felled eucalyptus, a rolled tarp, a broken toilet, a battery and a shattered TV.

A nearby field had turned black and sooty after the settlers burned it. The village school still stood atop a hill, its doors locked but all its windows smashed and removed. Inside the classrooms, learning and life stood still.

Perhaps the plaque with the names of the donors who helped establish the school – including EU foreign ministries and aid agencies – will serve to remind European states what happens to their taxpayer-funded contributions in the occupied West Bank.

Now, the community’s children have nowhere to study, with their school smashed and abandoned. In a video filmed on the last day of classes, a teacher asked one of her students: “Why are you leaving?” The student answered: “Because of the Jews.”

‘Move on and leave’

Here in Ein Samia, northeast of Ramallah, alongside Alon Road near the Kochav Hashahar settlement, a community of shepherds of the Kaabneh tribe lived with their sheep on private land leased from residents of a nearby village.

On the day the village was abandoned, the settlers’ online outlet, News of the Hills, wrote: “Good news! Two Bedouin encampments that have taken over areas near Kochav Hashahar in recent years are leaving the area! … God be praised, thanks to a large Jewish presence in the area and Jewish shepherds who reoccupied it, the Bedouins are leaving – hooray! We at News of the Hills wish that all the Bedouin would move on and leave the country. There is better pasture in Saudi Arabia, go there!”

Several kilometres north of Ein Samia, a makeshift dirt road leads to the new shelter. In one of the tents sits the elderly head of the community, Muhammad Kaabneh, a father of eight sons and 11 daughters with his two wives. As we speak, he is clear-headed and razor-sharp; his adult son Jasser occasionally joins the conversation.

The members of this community are refugees and children of refugees of the Negev (Naqab) lands from which they were expelled in 1948. From there, they moved to a community near Jericho, but were forced out again in 1967 towards Muarrajat. Three years later, they were expelled by the army and moved to a village where the Kochav Hashahar settlement was later established, pushing them out again to nearby Ein Samia.

Until two weeks ago, they lived there, growing from a population of 15 families in 1980 to more than double that today. But Israeli authorities have challenged them with demolition orders at every turn, destroying residential structures and livestock enclosures.

Then came the troubles with the settlers, who began grazing their own animals on the villagers’ fields – a proven method of terrorising residents and taking over their lands. Residents said they were attacked, threatened and beaten by settlers, as Israeli army and police forces refused to step in.

One community member was recently arrested and accused of stealing sheep from the settlers; later that night, settlers pelted the sleeping shepherds with stones. Their fields were set ablaze and residents estimate they lost a crop of two tonnes of grain.

The villagers decided they couldn’t take anymore. The expulsion process took about four days. “It’s all over; it’s all over,” their mukhtar said sadly.

The settlers are determined to prevent them from returning to salvage their belongings – just as the Israeli army prevented earlier deportees from returning to their homes after 1948, even if only to save their property.

Gideon Levy is a Haaretz columnist and a member of the newspaper’s editorial board. Levy joined Haaretz in 1982, and spent four years as the newspaper’s deputy editor. He was the recipient of the Euro-Med Journalist Prize for 2008; the Leipzig Freedom Prize in 2001; the Israeli Journalists’ Union Prize in 1997; and The Association of Human Rights in Israel Award for 1996. His new book, The Punishment of Gaza, has just been published by Verso.

Source: Middle East Eye. 15 June 2023