By Rayhan Uddin in London.

It’s late April 1948, in Haifa, northern Palestine.

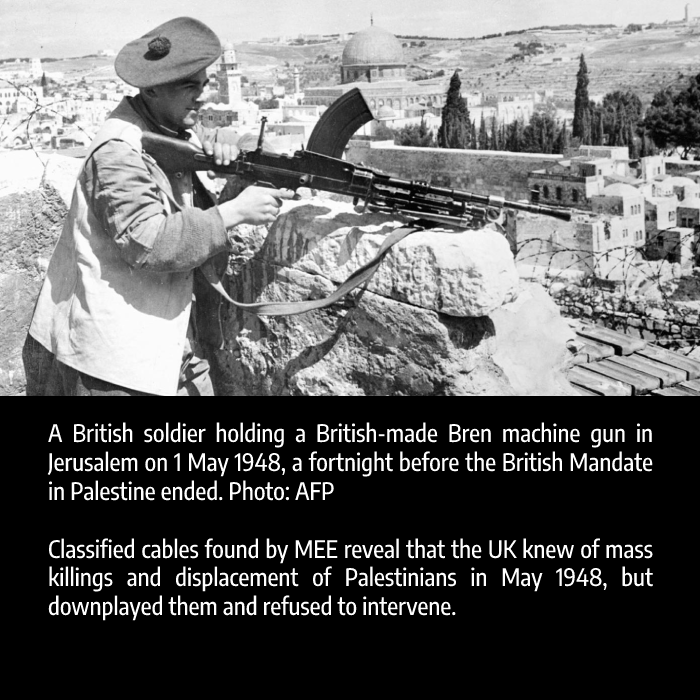

After more than 25 years, British officers are leaving their “mandate” over the territory and have set a withdrawal date: 15 May.

The exit is not going smoothly. Ethnic cleansing and violent atrocities are taking place across areas Britain is about to vacate.

Zionist armed groups, allowed to flourish in Palestine by the British over three decades and subsequently trained and armed by the colonial power, are sweeping across Palestinian towns and villages, forcibly displacing residents from house to house.

Palestinians put up some resistance, helped by nominal forces from neighbouring countries, but are vastly outnumbered and under-equipped. Britain states that it is remaining neutral.

Cyril Marriott, consul-general in Haifa, is one of the last British officials to leave the embattled city.

He wonders, in a 21 April diplomatic cable sent to London and seen by Middle East Eye, whether Britain’s reputation will be damaged by “abandoning the pretence of keeping law and order before the expiry of the Mandate”.

“Any loss of prestige we may suffer is insignificant compared with the strong feeling that will be aroused in the United Kingdom if heavy British casualties are caused by our armed intervention between Jews and Arabs,” he writes.

Months before Marriott’s cable, in November, the United Nations passed a resolution to split Mandatory Palestine into Jewish and Arab states – a policy Palestinian Arabs rejected.

Britain, which by then was coming under violent attack from the Zionist groups it had once propped up, declared it would leave by midnight on 14 May.

But 15 May 1948 would not just be remembered as the day that Britain left Palestine.

It was also the day that the State of Israel was declared, and the date generations of Palestinians continue to mark as the Nakba – or Catastrophe – 75 years later.

At least 13,000 Palestinians were killed and hundreds of villages were destroyed. In the end, 750,000 people were forcibly displaced from their homes.

More than 6,000 Israeli Jews, including 4,000 soldiers and 2,000 civilians, were killed.

Previously classified diplomatic cables, seen by Middle East Eye at the National Archives in London, show that Britain was well aware of mass killings and displacement, in Haifa and beyond, during the final days of its Mandate.

But London would play down the scale of the events, refuse to intervene or allow others to do so, and would eventually label Palestinians and their allies as masters of their own downfall.

Regional leaders warn of massacre

By the final days of April, leaders in Egypt and Syria were raising the alarm about the spiralling situation across their borders.

Azzam Pasha, an Egyptian diplomat and the Arab League’s first secretary-general, told British envoy Ronald Campbell in Cairo that Palestinians were being massacred in Haifa, Tiberias and Deir Yassin.

“This massacre was, [Pasha] was convinced, part of a Jewish military plan designed to terrorise the Arab population inside the Jewish state so that by May 15th they would be relieved of having to deal with any fifth column,” Campbell recounted to London on 22 April.

Pasha told journalists that same day, as transcribed in a British foreign office memo: “They have committed at Haifa acts as reprehensible as at Tiberias [and Deir Yassin] attacking women, children and old people. So far the British forces have displayed their inability to protect defenceless persons.”

On 9 April, in what became known as the Deir Yassin massacre, Zionist groups went house to house, killing over 100 Palestinians in the small village near Jerusalem, despite having agreed to an earlier truce.

Nine days later, Tiberias fell to Zionist militias too, where 6,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled.

Then on 21 April, Jewish paramilitary organisations ethnically cleansed Haifa, ejecting tens of thousands of Palestinians.

Phillip Broadmead, British envoy in Damascus, wrote to the foreign office on 23 April following a meeting with Syrian President Shukri al-Quwatli, who was disturbed by events in Haifa.

Quwatli complained to Broadmead that a local British commander in Haifa had refused “to take measures to stop the killing of Arab women and children”, unless Palestinians delivered all their arms to Zionist groups, as per a truce proposal rejected by the Arabs.

Damascus lamented that Britain had promised to maintain law and order by 15 May, but “the events at Deir Yassin and Haifa made it clear this was no longer the case”.

In Cairo, Pasha told Campbell that there was “a fully mobilised Jewish force in the country whose activities were out of control”, but no counter-balancing Palestinian force.

According to British figures at the time, there were around 15,000 troops from Iraq, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan, in addition to 5,000 volunteers from the Arab Liberation Army. They were comfortably outnumbered by over 70,000 Jewish troops.

Cairo pleaded with Britain to turn a “blind eye” and allow volunteer Arab forces to enter Palestine before the Mandate expired to provide that “counter balance” to the mass killings and ethnic cleansing. London refused.

Pasha told Campbell that if the British continued this stance until 15 May, “the result would be that Jewish forces would by that date have occupied all the strategic positions they required and the Arabs would find themselves at a great disadvantage”.

He was right. Arab armies did enter Palestine to push back Israeli military advances after the expiry of the Mandate, but by then most of the key areas of what is now modern-day Israel had been depopulated and taken over by Zionist groups.

‘Reports have been exaggerated’

Despite the warnings, British officials significantly downplayed the scale of what was happening, including in Haifa.

On 23 April, facing pressure from Arab governments, the foreign office wrote to its envoys in Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

“You should inform [the] Government to which you are accredited accordingly, and point out that previous reports have clearly been exaggerated,” it said. “In particular press stories of evacuation of 23,000 Arabs [in Haifa] are a considerable exaggeration.”

Five days later, junior foreign minister Christopher Mayhew would take to the floor in parliament and state: “Early reports of widespread massacre in the town [of Haifa] are untrue and were merely rumours caused by panic.”

Eventually, a few days later, British officials admitted in classified memos that the vast majority of Palestinian inhabitants had indeed left Haifa. The officials were nevertheless keen to promote the idea that those residents would return immediately.

“There are 6,000 Arabs in Haifa and many more are returning. Others wishing to return may be assured that under present conditions their security is guaranteed and that there is every reason to think that after 15th May they will be safe there,” said Alan Cunningham, then British High Commissioner in Palestine.

“We are giving publicity to the fact that many are returning in the hope that this will spread confidence.”

They did not return. The Palestinian population of Haifa was reduced from 70,000 to around 6,000 in a matter of days.

There are at least 250,000 registered refugees from Haifa living around the world, according to figures from 2008.

British officials parrotted the claim, which proved wholly untrue, that Jewish leaders would not allow for the mass evacuation of Palestinians due to the adverse impact it would have on the local economy.

“If the Jews press their terms too harshly the Arabs would be likely to evacuate Haifa, a course not welcome to the Jews as the life of the town would be interrupted,” a 23 April memo sent from Palestine to London stated.

“It is probable therefore that the Jews will temper their terms to prevent total evacuation.”

Britain appeared to be presenting a narrative contrary to the reality on the ground.

It asked its various envoys in the Middle East to remind Arab governments that British troops had engaged Jewish mortars, referring to military action taken against Zionist fighters in Jaffa.

British troops briefly halted Operation Hametz, an ultimately successful attempt to blockade Palestinian towns around Jaffa.

It was the first direct battle between British forces and Irgun, the militant right-wing Zionist organisation that had bombed the British administrative headquarters at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem two years earlier.

Following that confrontation, British officials claimed several times that “the morale of the Jews had considerably deteriorated, as Arab morale had risen”.

The 1948 forced expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland has created the longest unresolved refugee crisis in modern history.

READ: The Nakba: All you need to know explained in five maps and charts

Palestinian existence will ‘become precarious’

Any such high morale was short-lived. Zionist advances on Jaffa were only halted temporarily.

Britain knew, and admitted in private, that Palestinians stood no chance of remaining in the port city that would become part of Israel’s Tel Aviv.

In a top-secret telegram memo from late April, the commanders-in-chief of the Middle East Land Forces (MELF) predicted what would happen once its forces left the city.

“The Jewish community is firmly and securely established and once our own security forces withdraw there will be little question of the Arabs seriously threatening Jewish life or property,” they told the defence ministry back in London.

“Indeed, the existence of Arabs will become precarious.”

That assessment was correct. Jaffa was completely obliterated, with around 96 percent of Arab villages there destroyed by May 1948. Its entire population of over 50,000 Palestinian inhabitants were expelled, according to Ilan Pappe‘s The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine.

There are now over 230,000 refugees from Jaffa living across the globe.

In total, those expelled from Palestine in 1948 and their descendants number 5.8 million refugees, mostly living in neighbouring countries.

They have never been allowed to return, making it the longest unresolved refugee crisis in modern history.

British commanders in Palestine knew that Jewish groups would take control, not just of Jaffa, but in towns and cities across Palestine.

“Between now and the surrender of the Mandate[,] clashes are likely to intensify in numbers, scope and duration. In these clashes the Jews are likely to hold their own,” the Land Forces central command said.

“Ultimate success is likely to be with the Jews with their far greater material resources and intense unity of purpose.”

That superiority did not occur in a vacuum: during the Arab Revolt of the late 1930s, British forces weakened Palestinian society, including gutting its paramilitary forces.

Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi argues in The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, that Palestine was not lost in the 1940s, but the decade prior, by the British crushing of its civil and military institutions.

Britain blames Arab ‘ineptitude’

In the final days of the Mandate, in several different memos across a number of days, Britain’s ambassador claimed that Palestinians and their allies only had themselves to blame.

“Arab military forces in Palestine are now suffering the inevitable consequences of incompetent leadership and lack of discipline and morale,” said Cunningham.

“In their hearts the Arabs realise that their much vaunted Liberation Army is poorly equipped and badly led; they feel that their monetary subscriptions have been squandered and they themselves misled.

“They must pin blame on someone and who more deserving than the British!” he added sarcastically.

British military leaders also took aim at other Arab governments in the region, blaming them for provoking Zionist miltias.

“Foreign Arab irregular forces, having stirred up a hornets’ nest have now been prudently withdrawn, leaving unfortunate Palestine Arabs to be stung,” said Cunningham.

“The Jews for their part can hardly be blamed if in the face of past Arab irregular action and of continued threats of interference by Arab regular forces, they take time by the forelock and consolidate their position while they can.”

The military central command agreed with Cunningham’s appraisal of Arab forces, hitting out at their “cowardly behaviour” and “refusal to follow our advice to restrain themselves”.

On 15 May, Marriott, the consular-general in Haifa, was one of the few Brits to remain in the territory, after 100,000 officers had left in the days and weeks prior.

He gives a mistakenly optimistic final assessment.

“Jews control the town but their armed forces are little in evidence. They obviously want the Arab labour force to return and are doing their best to instil confidence,” Marriott said.

“Life in town is almost normal even last night[,] except of course for the absence of Arabs. I see no reason why Palestine Arab residents of Haifa and neighbourhood should not return.”

Seventy-five years later, those residents of Haifa and their descendants are still waiting for that return.

Source: Middle East Eye. 16 May 2023.