B’tselem publications.

The right to vote and run for office is fundamental to democracy. Without it, there is no democracy worthy of its name. This right is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which sets forth that “[e]veryone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.”

Yet holding elections is not enough. Totalitarian regimes also engage in a process they refer to as “elections,” but this does not make them democracies. Democratic elections must reflect core principles such as equality, liberty and freedom of expression. These allow not only the act of voting itself, but also the free exchange of ideas and meaningful participation in shaping the future. Democratic elections must also ensure one vote for every citizen that is exactly equal to all others, and allow all citizens to run for office, present their platforms and work to further their agendas. Legal restrictions on voting and on running for office must be extremely limited, if at all permitted.

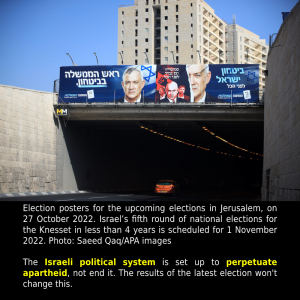

Israel’s upcoming general elections are being touted, as usual, as a ‘celebration of democracy.’ Below, we examine whether they indeed meet minimal democratic standards, and present some facts about the place we all live in.

Full political rights: for Jews only, in the entire area

All the Jewish citizens who live between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea can fully participate in Israel’s general elections. They can vote, run for office and promote their agendas in various ways. They can be elected for parliament and serve as ministers.

Currently, about 10% of all Jews living under the regime for which the elections are being held reside beyond the Green Line, in more than 200 settlements built throughout the West Bank. Thanks to the legal framework Israel instated, their right to political participation remains untouched despite living outside Israel’s sovereign territory, and they can vote and run for office like all Jewish citizens living west of the Green Line.

Settlers are not even required to cross the Green Line and enter Israel proper in order to vote. As far back as the early 1970s, the Knesset amended the law to allow citizens to vote in settlements. Polling stations are made available throughout the territory the Israeli regime controls – in the Jewish settlement in Hebron and in Ramat Aviv, in Ari’el and in Nof HaGalil, in Haifa and in Jaffa. The Central Elections Committee website displays results in all polling stations. Those stationed inside settlements appear on the same list as those west of the Green Line.

One regime, throughout the entire area.

Lesser political rights, if any: for Palestinians only, in the entire area

Palestinian subjects living under occupation in the West Bank and Gaza Strip cannot participate in elections

Roughly 5.5 million Palestinian subjects live in the territories occupied by Israel in 1967: about 3.5 million in the West Bank (including roughly 350,000 in East Jerusalem) and some 2 million in the Gaza Strip. None of them are allowed to vote or run for Knesset, and they have no representation in the political institutions that dictate their lives.

This reality persists despite the fact that Israel has been the sole power controlling and managing these millions of lives for more than 55 years. Israel controls the land, sea and air spaces and has retained key governance aspects despite geopolitical changes over the years. Israel cites these changes to support its argument that residents of the Occupied Territories can influence their future through other political systems – the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and the Hamas regime in the Gaza Strip. Yet this claim is detached from reality.

These are the facts:

In the Gaza Strip, after removing its settlements and withdrawing its military in 2005, Israel declared its rule over the area at an end and its duties towards Gaza residents terminated, barring minimal obligations aimed at preventing a serious humanitarian crisis. Hamas’ internal rule in the Gaza Strip may bolster this claim and help Israel ignore the 2 million people living there. Yet the fact is that Israel still holds almost all powers pertaining to Gaza residents and determines what their daily lives look like, in no small part due to its near-complete control over the movement of people and goods in and out of the Gaza Strip.

In the West Bank, Israel supposedly transferred some powers to the Palestinian Authority. It has since used this move to perpetuate an illusion that political power in the West Bank is divided, with Israel and the Palestinian Authority each acting independently and as it sees fit in the areas it controls. Israel works to uphold the perception that everyone in the West Bank has a political system in which they can participate: the settlers vote and run for Knesset and the Palestinians for the Palestinian Authority. However, the Palestinian Authority can only govern very limited aspects of life in Palestinian urban centers, and usually requires Israel’s permission even for that, while Israel retains control over all major aspects of life – including the use of force, incarceration, the justice system, planning and building, freedom of movement (to and from Israel, Jordan and Gaza, as well as within the West Bank), resources, the population registry and many more. Regardless of whether elections for the Palestinian Authority are held – there have been none in many years – the true control remains in Israeli hands.

In East Jerusalem, upon annexing the area, Israel gave Palestinians living there at the time permanent residency status. This status, which does not confer a right to run or vote for Knesset, is usually given to immigrants entering the country. In the case of East Jerusalem, the opposite is true: it was Israel that entered the area. Residents of East Jerusalem can, theoretically, become citizens and participate in general elections, but the process is lengthy and complex, and Israel deliberately puts bureaucratic obstacles in their way.

Palestinian citizens limited in exercising the right to vote and run for office

The roughly 1.7 million Palestinians with Israeli citizenship status can, like Jewish citizens, take part in the general elections. They can vote for their candidates, start their own parties or join existing ones. However, their political participation has been cast as illegitimate since the very inception of the state, along with attempts to restrict or deny them true political representation.

There is no shortage of examples illustrating the widespread view in Israel that Palestinians’ political participation should be monitored, controlled and curtailed, and that their right to vote and run for office should be drained of any meaning. The Military Rule imposed on Palestinian citizens until 1966 treated this entire population as enemies, severely restricting their political activity. Mapai (later the Labor Party), which governed the state and most of its institutions in Israel’s early years, refused to take on Palestinian candidates until the early 1980s and set up satellite parties for Palestinian citizens, dictating who would run in them and how they would vote. Efforts to de-legitimize Palestinian political participation continue to the present day, clearly showing that some of the Israel’s leaders and the public at large see such participation as undesirable. This sentiment was perfectly captured in various slogans used during election campaigns, such as “Netanyahu is good for the Jews” (1996), “No loyalty, no citizenship” by right-wing party Yisrael Beitenu (2009), or a clip released on election day (2015) in which then-Prime Minister Netanyahu warned that “the right-wing government is in danger. Arab voters are heading to the polling stations in droves”.

The underlying message is clear: the political participation of Palestinian citizens is not, and must not be, equal to that of Jewish citizens. It is often seen as an attempt to undermine the Jewish citizens’ monopoly on political power in the entire area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. That is also why Knesset resolutions that rely on votes by Palestinian MKs, without obtaining a Jewish majority, are widely considered illegitimate.

This is more than longstanding practice and rhetoric. The political participation of Palestinian citizens is also limited by Basic Law: The Knesset. Section 7a, legislated in 2002, stipulates that a candidate or a list of candidates can be barred from running for Knesset if their actions or goals explicitly or implicitly include “negation of the existence of the State of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state.” The Central Elections Committee – a body comprised of representatives of various political parties – has repeatedly relied on this clause to disqualify Palestinian candidates and lists, arguing that their civil struggle for full equality violates the clause as it denies Israel’s existence as a Jewish state.

In 2003, shortly after Section 7a passed into law, then-Supreme Court President Aharon Barak ruled that running for office is a constitutional right and that, therefore, the section must be interpreted narrowly such that lists will be disqualified only when there is “clear, unequivocal, persuasive evidence” and only when the goal is injurious to “the ‘core’ features that form the minimal definition of Israel as a Jewish state.” The Supreme Court has since repeatedly relied on this interpretation to reverse decisions made by the Central Elections Committee and to clear Palestinian candidates and lists to run in the elections.

Nevertheless, in these decisions, the justices repeatedly stressed the limits of Palestinian political participation. President Barak, for instance, explained that demanding equality does not threaten the existence of Israel as a Jewish state only so long as the aim is to “secure equality between citizens internally, while acknowledging the rights of the minority living among us.” If, on the other hand, the demand for equality “seeks to undermine the rationale for the country’s establishment, thereby denying Israel’s character as the state of the Jewish people, then it is injurious to the core, minimal features that make Israel a Jewish state.” In this case, there is room, he held, to consider disqualifying a list or candidate supporting this position.

In June 2018, the Balad party submitted a bill titled Basic Law: A Country of All Its Citizens while the Knesset was debating a bill titled Basic Law: Israel – the Nation State of the Jewish People. Balad’s bill was intended to enshrine “the principle of equal citizenship for all citizens, while recognizing the existence and rights of both national groups – Jewish and Arab.” In a rare move, the Knesset Presidium refused to admit the bill, thereby blocking debate on the matter in the plenum.

Though the bill was never even debated in the Knesset, submitting it clarified the breadth and scope of equality sought. Supreme Court President Esther Hayut ruled that merely proposing the bill crossed a red line and was “a significant act by Balad MKs sitting in the 20th Knesset, attempting to effect, through a bill, a political program and worldview that negate the existence of the State of Israel as a Jewish state.”

Justice Hayut also ruled that this position could have justified disqualifying the party, but stopped short of banning Balad for technical reasons (partly because a disqualification would also apply to the Ra’am party, which ran jointly with Balad). In a recent hearing regarding Balad’s disqualification, in the run-up for the upcoming elections on 1 November 2022, President Hayut repeated these remarks, once again describing the bill as a “watershed moment” and “very, very problematic.”

The message to Palestinians and their candidates is clear: Do not seek full equality and recognition of collective national rights. Demanding equality on matters such as land, immigration and national emblems is perceived as repudiating Israel’s constitutional principles, as it undermines the country’s definition as a Jewish state. Prime Minister Yair Lapid recently spelled out this principle, saying: “Twenty percent of the population are Arabs. We can and should give them civil equality… On the other hand, we will not give them national equality, because this is the only state the Jews have.”

Palestinian citizens who choose to participate in the electoral process have no choice but to enter the political playing field with their hands tied. The parties representing them are barred from challenging the fundamental principles of the regime that is dispossessing and oppressing them. They cannot seek to abolish the laws and systems that harm them, which are considered defining features of the Jewish state. They cannot fight for a core democratic tenet: full equality for all those living under the same regime. This limits political participation exclusively for Palestinian citizens. No matter what they do or how they vote – constitutionally, their vote is worth less.

Clearly, curtailing the right to political participation (of Palestinian citizens) is different from denying it altogether (from Palestinian subjects). Palestinian citizens who choose to participate in the general elections can still take part – although to a lesser extent than Jewish citizens – in fighting Israel’s regime of supremacy, control and oppression, and in promoting full rights and a democracy that is not inherently hollow.

This is apartheid

Roughly 15 million people, about half of them Jews and the other half Palestinians, live between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, under a single rule. The perception that there are two separate regimes in this territory – a democracy on one side of the Green Line, within Israel’s sovereign borders, and a temporary military occupation on the other – is divorced from reality.

All of us, Jews and Palestinians alike, live in this area in a binational reality, under a single regime. However, not everyone will be permitted to vote in the coming elections, which will determine the government and our lives in the coming years. About half of the population – all the Palestinians who live in this area, whether they are citizens, permanent residents or subjects – are either fully or partially excluded from this decision-making process.

One regime governs the entire area and the fate of everyone in it. This regime operates according to a single organizing principle: advancing and cementing the supremacy of one group – Jews – over another – Palestinians. Under this regime, Jewish citizens have the monopoly on political power. Only they have a true seat at the table where their fate, and the fate of Palestinians, is determined.

This is not a democracy. This is apartheid.

Source: B’tselem. 31 Oct. 2022

RELATED: