By Charles Pierson.

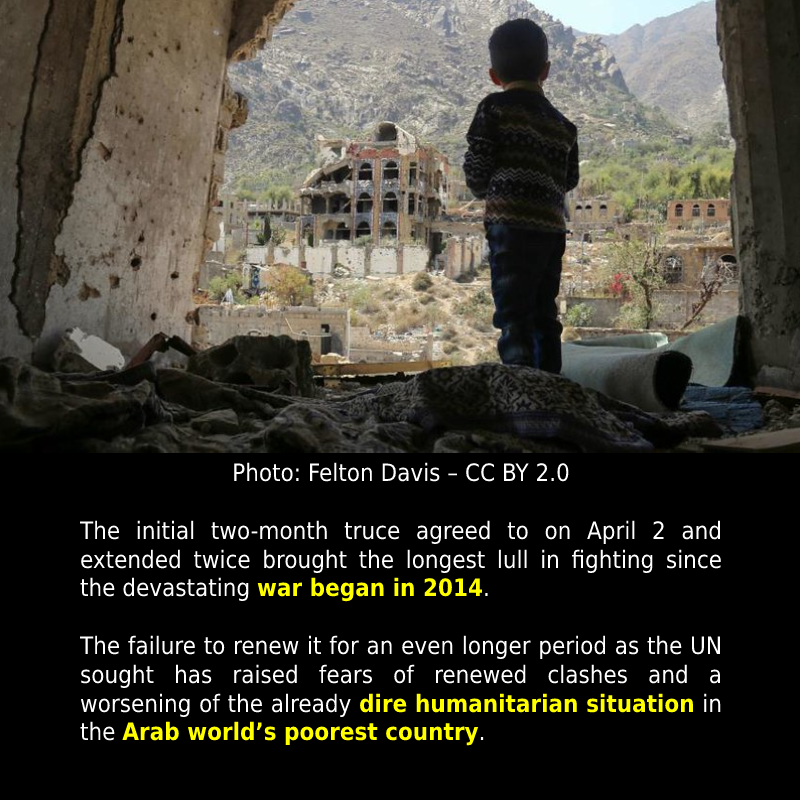

Hope for peace in Yemen dimmed on October 2 when a truce between a Saudi-led coalition and Yemen’s Houthi rebels expired without being renewed. The truce had begun in April, was extended in June, and extended again in August.

Since 2015, the US has been Saudi Arabia’s silent partner, providing the Saudi-led military coalition (“SLC”) with intelligence and targeting assistance, and (until November 2018) conducting in-flight refueling of coalition aircraft. Yemenis refer to the “Saudi-American war,” or, simply, the “American war.”

Biden had promised to end US assistance to the coalition, both on the campaign trail and in his first major foreign policy speech as president on February 4, 2021. Biden has scaled back US assistance, but the US continues to sell massive quantities of arms to the Saudis and Emiratis.

The US also provides spare parts and maintenance for coalition warplanes. Experts, such as Bruce Riedel of the Brookings Institution, contend that without US maintenance and spare parts, Saudi warplanes would be “grounded.” Grounding the Royal Saudi Air Force would end the kingdom’s massively destructive bombing campaign. It might even end the war.

Congress Can End the War in Yemen. Will It?

Yemen’s belligerents have been unable (so far) to end the war. Biden could end US assistance to the Saudis, thus crippling their war effort and perhaps forcing a peace, but Biden hasn’t. Who is there left who can end the war? Can Congress?

US participation in the war in Yemen was not approved by Congress as the Constitution requires. Congress can force the executive to end its unconstitutional assistance to the SLC by passing a War Powers Resolution (WPR). On June 1, H.J.Res. 87 was introduced in the House of Representatives by Representatives Pramila Jayapal (D-WA7) and Peter DeFazio (D-OR4) along with forty other House members. H.J.Res 87 requires the US to end intelligence sharing with the SLC as well as logistical support, “including by providing maintenance or transferring spare parts to coalition members flying warplanes engaged in anti-Houthi bombings in Yemen.”

The War Powers Resolution must be passed by both chambers. A companion to the House resolution, S.J.Res 56 was introduced in the Senate on July 14 by Senators Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Patrick Leahy (D-VT), Elizabeth Warren (D-MA). Neither resolution has been scheduled for a vote yet.

The chances of the Yemen WPR passing are slim. Congress tried to pass a War Powers Resolution for Yemen as recently in 2019. That WPR made it through Congress, but was vetoed by then President Donald Trump. We should expect a veto from President Biden if Congress passes a new WPR. If Biden does not veto the War Powers Resolution he will be admitting that his Yemen policy has failed.

Overriding a presidential veto requires 67 votes in the Senate and 290 votes in the House (two-thirds of each chamber). Where are those votes going to come from? The Senate is currently split evenly between Republicans and Democrats. If all Senate Democrats vote to override a Biden veto, they will need 17 Republican votes. I repeat: where will those votes come from? In 2019, seven Republicans joined all Democrats in voting to override Trump’s veto. That was ten votes short of what was needed. Will any Republicans be willing to support a new WPR?

Besides admitting that his Yemen policy has failed, the president has an additional motive for vetoing the WPR: placating Saudi Arabia. On October 2, OPEC+ (the 13 members of OPEC and 10 nonmembers, including Russia) announced that it was cutting oil production by 2 million barrels a day. The price of gasoline per gallon soared after Biden’s March 8 embargo on Russian petroleum and natural gas in response to Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine. After reaching a peak of $5.01 per gallon (national average) on June 14, 2022, prices steadily declined, bottoming out at $3.67 per gallon on September 20. OPEC+’s October 2 announcement guarantees that gas prices are headed up again. High gas prices could spell disaster for Democrats heading into the midterms which are now less than thirty days away.

In July, President Biden traveled to Riyadh to meet with Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (“MBS,” in popular parlance). Although Biden says that he did not discuss the price of oil with MBS, it’s more likely that Biden pleaded with MBS to open the taps full blast. If so, he was disappointed.

We must assume that MBS has not forgotten—much less, forgiven—Biden’s numerous affronts. During the November 19, 2019 Democratic presidential debate, Biden called Saudi Arabia a “pariah state”; vowed to make the Saudis “pay the price” for the assassination of dissident Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi; and vowed to sell no more weapons to the kingdom.

Once installed in the Oval Office, Biden released a 2018 US intelligence report implicating MBS personally for ordering Khashoggi’s death. For months after taking office, President Biden refused to speak to MBS, instead insisting on dealing directly with the prince’s father, the ailing 86-year-old King Salman.

Besides personal animus toward Biden, MBS has another motive for keeping oil prices high. It is the kingdom’s growing closeness with President Vladimir Putin’s Russian Federation. Putin wants high oil prices in order to fund his war with Ukraine and to counter the West’s economic sanctions on Russia. MBS, who is no supporter of the embattled Ukrainians, is happy to oblige.

So, Biden is unlikely to talk MBS into cutting production. But Biden is not going to throw away that slim chance by allowing the War Powers Resolution to become law, which would alienate MBS further.

The obstacles to Congress passing a new War Powers Resolution are so steep that doing so may be impossible. It seems to me that the only people who can end the war are the Saudis and Houthis themselves. This is one reason why the failure to renew the truce is so devastating. The truce may have been Yemen’s last hope for peace.

Source: CounterPunch. 13 Oct 2022