By Azad Essa.

A quarter of a century ago, an Israeli graduate student studying the impacts of the Nakba on several villages near Haifa found himself talking with Israeli veterans who openly detailed their role in a massacre.

In his quest to get to the bottom of what happened at Tantura in May 1948, the graduate student, Teddy Katz, interviewed around 135 people, both Palestinians and Israelis, collecting 140 hours of testimony for his thesis at the University of Haifa.

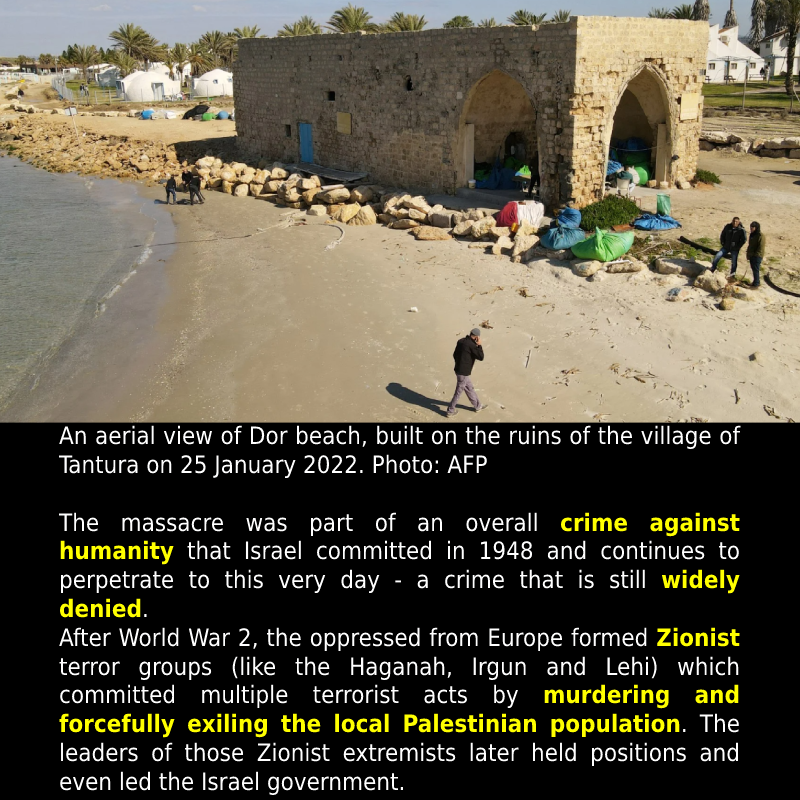

His subsequent dissertation detailed how the Alexandroni Brigade, one of a dozen brigades established by the Zionist paramilitary organisation known as the Haganah, had massacred up to 250 Palestinians after the village had fallen.

Katz determined through personal testimonies and eyewitness accounts that the Israeli soldiers had dumped the slain Palestinian bodies into mass graves. His thesis was published in 1998, and he received glowing academic reviews.

In January 2000, a journalist found his thesis and published extracts in the Israeli Maariv newspaper, prompting widespread denial and outrage.

Katz was accused by his interviewees of misrepresenting their stories, and they sued for libel. Katz found himself recanting his findings. Days later, Katz told the court that he had felt pressured to do so and wanted to defend his thesis. But it was too late; the case was closed.

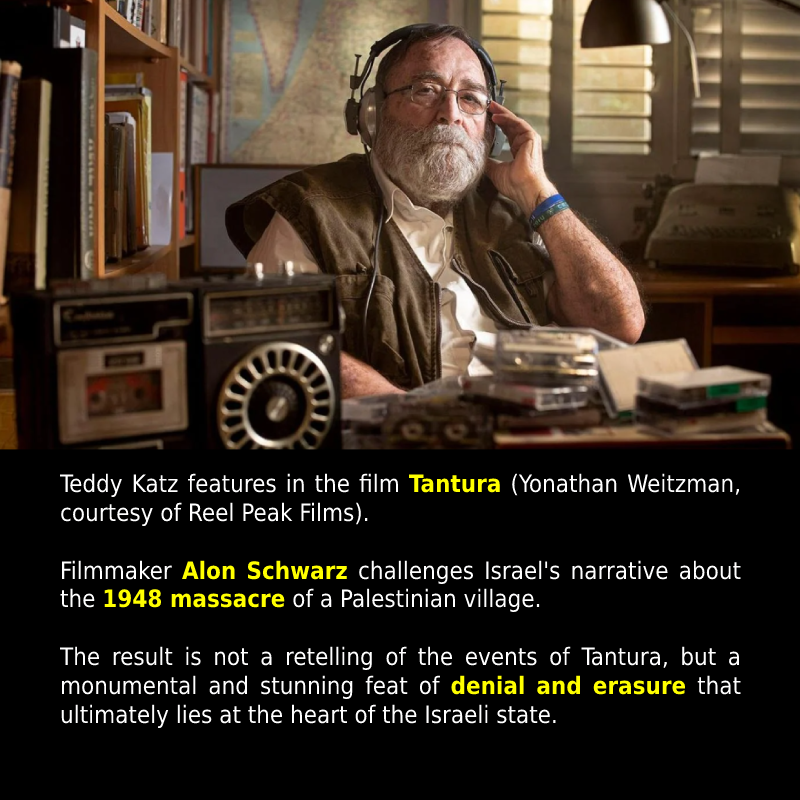

The university revoked his degree and Katz faded into obscurity. He lost his health. But he kept the tapes. Katz is one of the central characters in a stunning new documentary called Tantura by Israeli filmmaker Alon Schwarz.

Schwarz was initially working on a different documentary about human rights activists from Israeli NGOs opposing the occupation, when he met Katz, and decided to listen to the personal testimonies of murder and rampage conducted by Zionist militia members recorded on Katz’s tapes.

Among the interviews he would have heard is the testimony of an Alexandroni militiaman who took part in the Tantura raid: “Some of these young soldiers I remember – it’s not nice to say – they put [the Palestinian villagers] in a barrel and shot at the barrel, and I remember the blood in the barrel.”

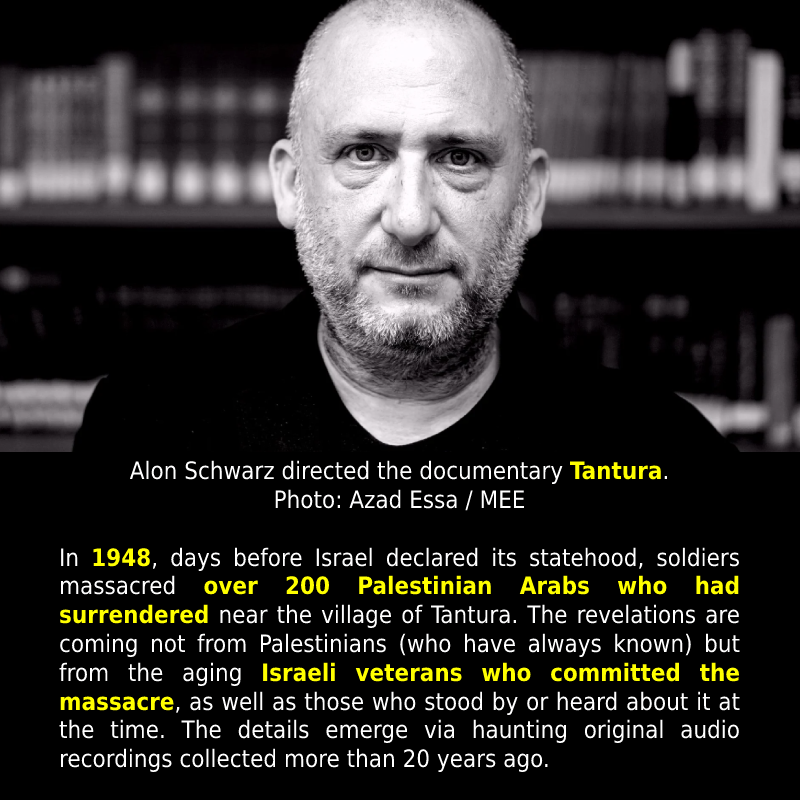

Schwarz decided to focus on Tantura instead.

‘I don’t remember’

He tracks down the surviving veterans – now well into their late 80s and 90s – to talk about the events of 1948, which Israel calls the “War of Independence”, and which Palestinians describe aptly as Al Nakba (The Catastrophe).

The former militiamen call the massacre “a rumour” and “a myth”; one veteran repeats that “there was no massacre”.

Schwarz also speaks with several Jewish women who took over homes in Tantura in June 1948, asking them about the stories they remembered hearing. The result is not a retelling of the events of Tantura, but a monumental and extraordinary feat of denial and erasure that lies at the heart of the Israeli state.

“To this day, the vast majority of what happened in 1948 is not only hushed up but destroyed,” Katz says in the film. “I found seven Jewish people who said there was a massacre [at Tantura]. But later, they all fell into line and denied it.”

In one scene in Tantura, Schwarz meets Gavriel Kofman, a former Alexandroni soldier, and plays a recording of another former militiaman telling Katz about a company commander who “shot one Arab after another with his gun because they didn’t give up their weapons. He shot them one by one with his Parabellum.”

But Kofman interjects to deny this ever happened. “I don’t know what to say. I don’t remember, maybe I saw, but I don’t remember,” he says. “That’s not who we are. Shooting in the head with a Parabellum, that’s exactly what the Nazis did. I don’t believe that.”

Revealing the truth

As the interviews go on, Shwarz continues to gently probe and prod, without ever taunting his elderly subjects – many of whom pause, laugh nervously, or contradict themselves.

The denials begin to peel back the truth, and Schwarz understands he is sitting on a landmine of secrets. This is where the film takes off.

Schwarz begins to conduct his own research. He consults old maps; interviews historians who supported Katz, such as Ilan Pappe; speaks with detractors, such as history professor Yoav Gelber, who have remained steadfast in their denial of the Tantura massacre; and discovers that Drora Pilpel, the judge who presided over the libel suit issued against Katz, hadn’t even bothered to listen to the tapes before shutting down the case.

Schwarz also employs satellite imagery to prove the existence of a former mass grave in Tantura, where Palestinians said the Zionists had buried the dead after the massacre.

“They killed many people. They removed them from their homes in pajamas. They took them like cows in front of them and killed them,” Ahmed Saleh Zaraa, a Palestinian originally from Tantura, told Katz in one of the recordings that Schwarz resurfaced.

Bodies ‘scattered like garbage’

At a certain point, it becomes clear that Schwarz is no longer presenting the massacre as a possibility. It becomes a fact that stands alongside the direct orders from David Ben-Gurion, who headed the Haganah paramilitary forces, to drive Palestinians out of their villages.

There are accounts of Alexandroni fighters lining up Tantura residents and shooting them dead; of them raping at least one Palestinian teenage girl and killing her uncle who stood up for her; and of them randomly opening fire on Palestinians, or chasing them with flamethrowers and incinerating them.

One former fighter with a Stalinesque moustache tells Schwarz he can’t remember how many Palestinians he killed: “I didn’t count. I can’t really know. I had a machine gun with 250 bullets.”

Their bodies “were scattered like garbage on the roads, the paths, between the houses”, says Yaakov Haleli, a former fighter with the Alexandroni brigade.

In an interview with Middle East Eye in New York City, Schwarz said the reality was that most Israelis were unaware of the details of the country’s birth in 1948. “Most Israelis don’t know what happened in 1948. Most Israelis believe the naive story that the Palestinians ran away in 1948 by themselves … because they were told by their leaders to do so,” Schwarz said.

“They don’t know that the Israeli army [Zionist militias] went into village after village and drove the people out, sometimes committing war crimes, like the massacre in Tantura. It’s not taught in school.”

Right of return

As a film, Schwarz’s Tantura is a momentous feat that looks to plug that gap. To watch the same Zionist militia that helped to build Israel through acts of ethnic cleansing struggle with the dissonance of their allegiance to the beloved Zionist state is documentary gold.

But as the film reaches its apex – in which it becomes abundantly clear that Tantura was part of the larger erasure of the Nakba – the film loses its way.

Having established that Israel was built on a set of foundational myths that involved the mass murder and expulsion of Palestinians, and then the erasure of these crimes, Schwarz suggests that resolving this conundrum requires Israel to openly discuss its history in a manner more appropriate for a democracy, akin to other settler-states, such as the USA or Australia.

He also asks some of his Israeli interviewees whether they think it’s time for a monument in Tantura.

But Palestinians who were driven out of their villages in Palestine don’t want a monument. Palestinians aren’t interested in Israelis beginning their dinner parties or academic conferences with land acknowledgements.

Palestinians want to return home. Why not suggest their right to return, I ask Schwarz?

“It’s very naive to think that Israelis are going to give this up. They are not. Not in the next 50 to 100 years. Israelis and Jews need their little corner in the world to be safe in. And we are not going to give this up. It’s not going to happen,” he said.

“We [are] gonna die and kill everybody else before it happens … that’s the DNA of Israel. I know this DNA because I am part of it,” Schwarz added. “So it’s very nice to ask, ‘Why don’t you want the Palestinians back?’ We don’t want them back because it threatens our lives. That’s how we see it.”

Tantura is as much a saga about the ongoing denial of the Nakba as it is about the refusal to mete out justice

Seven decades late

And herein lies the tragedy of the film. Whereas Tantura could have been used as a gateway towards discussing justice and redress, Schwarz is limited by his resolute belief in Zionism as fundamentally good and necessary for Jews.

“To Israelis, Zionism is the core,” he said. “It’s what brought us back from a nation that was put on trains and in gas chambers to a nation that can live safely in a spot of its own in the world. For Palestinians, Zionism is a terrible word. It’s a people who kicked them out of their homes.”

And the film suffers for it.

That the filmmaker who painstakingly exposed how Israeli society, with the full backing of the Israeli academy, government and armed forces, systematically erased the history of the native population in creating the powerful myth of Israel, is unable to extricate himself from the narrative, is a testament to the power of the myth itself.

I suspect it’s not through a lack of trying. Schwarz is against the occupation and considers Israel an apartheid state.

But Tantura is as much a saga about the ongoing denial of the Nakba as it is about the refusal to mete out justice. For Palestinians, the revelations in Tantura only reinforce what they have said all along about the Nakba. After all, Tantura was just one among hundreds of villages from which more than 700,000 Palestinians were expelled.

In the end, the film, though extremely important, is neither liberating nor a validation of their pain. It’s just 74 years late.

WATCH: Tantura is available to watch on demand on the video streaming site Vimeo.

READ: Tantura, BDS and surveillance in focus at ‘Other Israel’ film festival in New York

Source: Middle East Eye. 15 Dec. 2022