By Jonathan Steele.

The two hot wars of today’s world, the conflicts in Ukraine and Sudan, have stolen the limelight from what should otherwise have been a major news story and the trigger for a torrent of comment and debate.

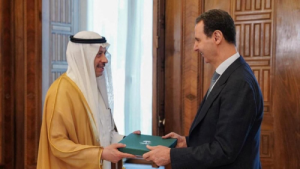

This is the Arab League’s recognition that Syria’s 12-year war is over, dramatic evidence for which is the Arab leaders’ invitation to Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad to rejoin the club.

The shift of policy has been gestating for more than a year and accelerated last month. It has wrong-footed the United States and western governments and given them a dilemma.

Do they follow the Arab leaders in deciding that engagement with the Syrian government is the best way to help the country rebuild and create the conditions for millions of Syrian refugees to return home safely? Or do they try to prevent this?

So far the omens are not good. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken insists the US will pursue “no normalisation” with Syria. Reaction in the US Congress has been even worse. A bill has been introduced to extend the so-called Caesar sanctions on Syria from running out in 2025 and keep them until 2032. These penalise any investor from any country who helps in rebuilding Syria’s infrastructure.

Under the Donald Trump administration, the US accepted publicly what Barack Obama had already conceded privately – that as a result of Russia’s military intervention in 2015, Assad would not fall.

Nevertheless, for motives that smack of utter cynicism, the US would maintain anti-Syrian sanctions and keep a contingent of some 900 troops in northeastern Syria in alliance with Syrian Kurdish forces.

Major Saudi policy shifts

This negative US policy now has a Ukrainian dimension, according to William Roebuck, a US diplomat who was recently embedded with US forces in Syria.

“The US wants to stay in Syria and keep troops there in order to deprive Assad and Putin of any sort of win,” he told a Quincy Institute webinar last week.

Joshua Landis, a professor at the University of Oklahoma and a well-known expert on Syria, told the same webinar: “The major thrust of American policy is not to allow Syria to rebuild. The Caesar sanctions are designed not to allow companies and outside foreign investment to rebuild the electricity grid, repair schools and rebuild the state, but to keep Assad weak and hurt the Russians and the Iranians.”

Though Syria’s return has spurred optimism about economic relief, experts are saying that for now the positives for Damascus are purely political.

Ten years ago, Saudi Arabia was financing and helping to arm the opposition to Assad. Its U-turn is remarkable.

Re-engaging with Assad is the third major shift of policy that Mohammed bin Salman has launched in recent months. The first was the decision to observe a ceasefire in Yemen and talk to the Houthis. The second was to re-open relations with Iran. Now comes the new policy on Syria. Equally remarkable is that the Saudis are challenging US objectives and taking independent decisions.

While the Saudi shift was the main driver in the invitation to Assad to rejoin the Arab League, other Arab states, in particular Jordan and Lebanon, have good reasons to support the move.

Now that fighting has largely ended in Syria, they want to reduce the social and economic burden of the refugees they have been hosting and get them to go home. This will entail some sort of amnesty or guarantees from Assad that returnees will not be prosecuted or harassed.

Arab governments also want to use the prospect of reconstruction money as a bargaining chip to persuade Assad to end the production in Syria of the addictive Captagon pills, which are smuggled into Jordan, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia.

King Abdullah of Jordan promoted his own peace plan on similar lines earlier this year.

Anger and despair

A big question is whether the new Arab League strategy is also adopted by Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who used to be a hawk in calling for Assad’s departure.

His triumphant re-election for another five years ought to make it easier for him to dump the old policy and re-engage with Assad. The Russians have been pressing both men to reconcile.

This will require a deal in which Erdogan withdraws his troops from the border regions of northeastern Syria in return for the Syrian army to re-deploy there. The Turks came in originally to expel Syrian Kurdish forces.

If Assad wants to reduce tensions and see the Turks pull out, he will have to make a deal with the Syrian Kurds as well as with Erdogan. This may mean granting them substantial autonomy.

Rather than the US keeping forces in Syria on an open-ended basis, as it seems to be intending to do, Washington ought to be encouraging the Kurds to engage with Damascus as a prelude to a US withdrawal.

The Arab League’s U-turn on Assad is a game-changer of enormous proportions. For millions of Syrians, it will be a source of huge disappointment as well as anger and despair. They had hoped the protest movement which began 12 years ago was going to bring democratic reform, if not a complete change of regime.

When elements of the movement took up arms and foreign states began to support them, many Syrians wondered whether this was a strategic blunder. They feared that the militarisation of the uprising would play into Assad’s hands as well as make Syria a battleground for foreign states to conduct proxy wars with their own agendas. And so it proved.

Twelve years later, the balance sheet is grim. Six million Syrians are refugees. Another six million are homeless inside their own country. More than half a million have lost their lives. Towns and cities have been destroyed. Nothing positive has been achieved.

Yet there is now the faintest glimmer of hope. If the Arab League governments, with their immense oil and gas wealth, are really willing to help Syria rebuild and not just host Assad for summit meetings, the chance for a new beginning is at last in place.

Jonathan Steele is a veteran foreign correspondent and author of widely acclaimed studies of international relations. He was the Guardian’s bureau chief in Washington in the late 1970s, and its Moscow bureau chief during the collapse of communism. He was educated at Cambridge and Yale universities, and has written books on Iraq, Afghanistan, Russia, South Africa and Germany, including Defeat: Why America and Britain Lost Iraq (I.B.Tauris 2008) and Ghosts of Afghanistan: the Haunted Battleground (Portobello Books 2011).

Source: Middle East Eye. 8 June 2023