By Linah Alsaafin and Maram Humaid.

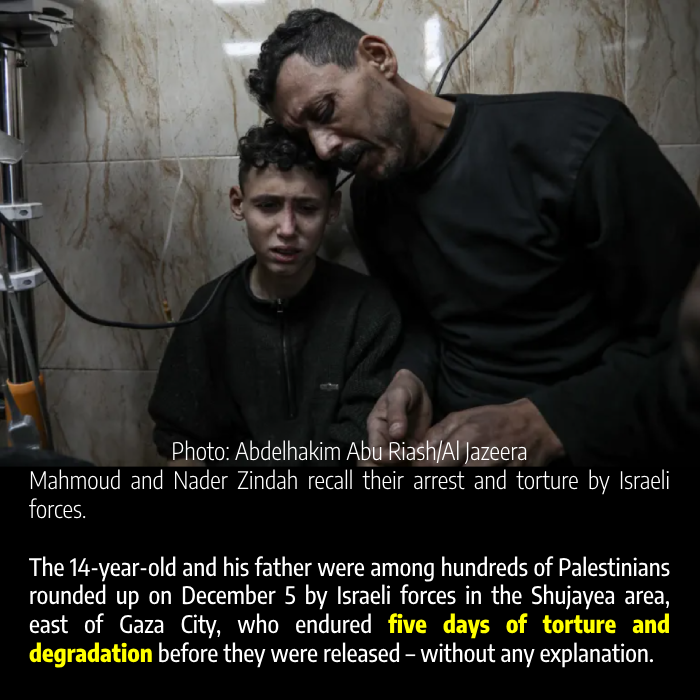

Deir el-Balah, Gaza Strip – Inside one of the rooms of Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital, Mahmoud Zindah stays close to his father, Nader, the horrors of the past week etched on both of their faces. Their eyes are wide, darting around.

“One of the soldiers said I looked like his nephew and that this nephew was killed in front of his grandmother who was taken hostage by Hamas and that the soldiers will slaughter us all,” Mahmoud says, his voice trembling.

Before their ordeal, the Zindah family was trapped in their home in the Zeitoun neighbourhood of Gaza City for two days, unable to leave as tanks advanced and artillery shelling got closer and closer. Those who dared to leave their homes for whatever vital errand were shot down in the streets by snipers.

On the third day, the family, who slept on the cold tile floor under mattresses to shield them from potential flying shrapnel, woke up to find the tanks on their street.

“We heard the soldiers shouting and the tank tracks getting louder,” Nader, 40, says. “I felt like there was something wrong, so I went to the house behind me, which was farther from the street. Before I reached it I stopped in shock. The house was moving!

“Then I realised that the Israeli bulldozer was knocking its walls down” and soldiers were firing live ammunition as well, he adds.

Nader quickly tore some white sheets into small “flags” for each of his eight children to carry. They poked one out of their front door, as the adults shouted that there were people in the house. The bulldozer stopped, as did the shooting. But suddenly the home was full of Israeli soldiers.

“They made us empty out our bags on the floor and blocked us from picking up our money or our wives’ gold,” Nader recalls. “What little food we had, they also threw away. They took our money, IDs and phones.”

The soldiers divided the household: women and young children in one room and the men and teenage boys in another. Then they told Nader, Mahmoud, his brother-in-law and another male relative to strip, then pushed them outside.

“They rounded up at least 150 men from the surrounding homes and blindfolded and handcuffed us all in the street,” Nader explains.

When the soldiers forced the men onto the backs of some trucks, Nader made sure Mahmoud was on his lap, terrified of what they would do to his son if they were separated.

“I don’t want to lose my child, nor do I want my son to lose his father,” he says.

The men quickly realised that there were also women in the truck, which kept braking suddenly, sending the prisoners falling on top of each other.

“We were all blindfolded, so we couldn’t see each other, but we heard the women telling us to look out for them like we would for our own sisters,” Nader says. “There were also younger children with them.”

The truck stopped, and once again, the men and women were separated. The men and teenage boys were taken to a warehouse where they sat on a bare floor covered in scattered grains of rice. There they were beaten, interrogated and verbally abused. There was no sleep, and the grains of rice cut their skin as they sat there, undressed.

Starved and beaten for days

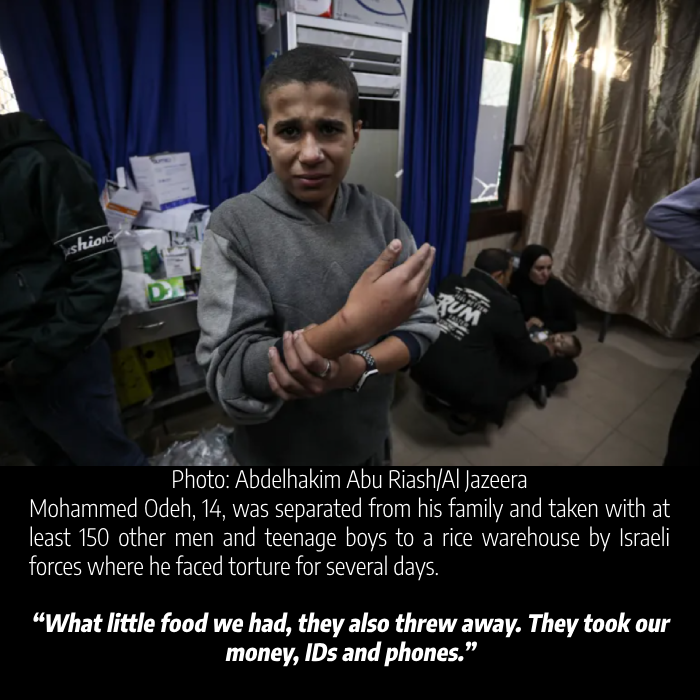

Mohammed Odeh, 14, was taken from the same Wadi al-Arayes neighbourhood in Zeitoun as the Zindahs, where he and his family were stuck in their homes for five days, starving.

Two of the neighbourhood boys who left to look for water were killed on the street by Israeli snipers. After the bulldozer knocked down the walls of several homes, the soldiers dragged the men and teenagers out, slapping, punching and hitting them with their guns.

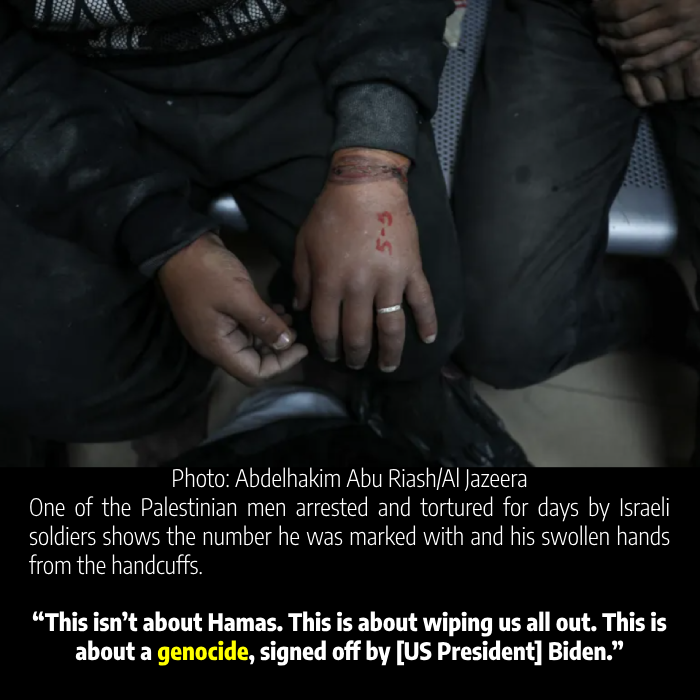

“There was no reasoning with them,” Mohammed recalls. “They kept saying, ‘You are all Hamas.’ They wrote numbers on our arms. My number was 56.” When he stretches his arms out, the red marker is still visible on his skin.

“When they spoke to us in Hebrew and we wouldn’t understand, they’d beat us up,” he continues.

“They hit me in the back where my kidneys are and my legs. They took my family, and I don’t know where they are,” he says, his voice breaking.

Before they were forced inside the warehouse, Israeli female soldiers came and spat on the men, Mohammed recalls.

In the warehouse, it was common for groups of five soldiers to suddenly enter and beat one person while the others were forced to listen to his screams of pain. If any of the men and teenagers nodded off from exhaustion, the soldiers poured cold water on them.

“Their contempt for us was unnatural, like we were lesser beings,” Mohammed says.

“Some people didn’t return from the torture sessions,” Nader says darkly. “We would hear their screams and then nothing.”

At one point, Mahmoud told his father that his wrists were bleeding from the handcuffs. A soldier overheard, asked where it hurt and then proceeded to press down on the spot. Nader tried to shield his son, and one of the soldiers tried to drag the teenager away. When Mahmoud resisted, he was kicked in the face. The mark is still visible.

“My dad kept shouting at them that I’m a child and threw himself on top of me,” he says. “I heard a soldier speaking in an American accent, and I told him in English that I’m just a kid that goes to school.” Their words fell on deaf ears.

Blindfolded and handcuffed the entire time, the men and boys endured hours of beatings.

“They cursed at us, spewing the most foul language,” says Nader, who suffered a particularly painful blow to his head. “Some of them spoke Arabic. Every time you tried to talk, asking to go use the bathroom or wanting a drink of water, they would come and beat us up, using the butts of their M16 rifles.”

The soldiers interrogated them and threatened to kill them all. They accused the Palestinians of stealing their army jeeps and raping Israeli women. When they asked Mahmoud where he was on October 7 and he answered that he was sleeping at home, the soldiers hit him, he says.

“They have this unbelievable racism. They really hate us,” Nader says. “This isn’t about Hamas. This is about wiping us all out. This is about a genocide, signed off by [US President] Biden.”

The men were given only a few drops of water and some scraps of bread to eat. Some were forced to relieve themselves on the spot while others were handed a foul-smelling bucket.

On the fifth day, Saturday, Nader, Mahmoud, and 10 other men were taken to Nitzarim, a former settlement south of Gaza City that had been turned into farmland after the 2005 Israeli disengagement. It is now an Israeli checkpoint just before Wadi Gaza and the men were released there and told to head south.

The group took off their blindfolds and let their eyes adjust to the light after days of darkness. They were exhausted and hungry and still did not have any clothes. After walking painfully for two hours, a group of Palestinians spotted them.

“They clothed us and gave us water,” Nader says. “An ambulance was called, and we arrived at Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital, where we were immediately given IV fluids.”

“I thought I didn’t have a chance of getting out alive,” he adds.

“It was hell on earth. It was like spending five years in that warehouse. I wouldn’t wish this on anyone.”

Source: AlJazeera. 131223