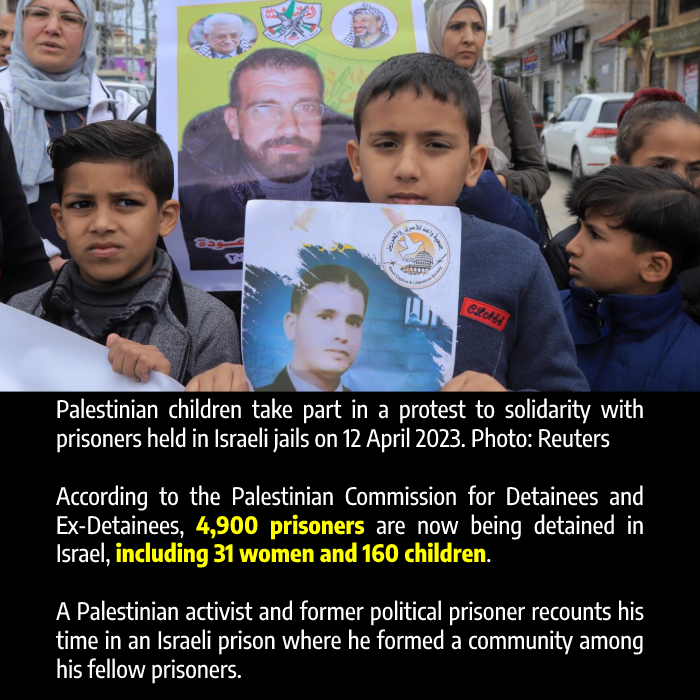

By Ameer Makhoul.

Like thousands of Palestinians who experienced arbitrary arrest and detention by occupation forces, I was incarcerated in an Israeli prison for nearly a decade. As Palestinians mark Palestinian Prisoner’s Day on 17 April, I look back on my ordeal which began on 6 May 2010.

I was arrested in a pre-dawn raid by armed police who stormed my house after jumping over my fence and practically breaking down the front door. As soon as they entered, they separated me from my wife and two daughters. I was surrounded by several security agents, some of whom exposed their faces while others hid behind masks. At that moment, I became a prisoner in my own home.

A Shin Bet (Israeli Security) agent from Haifa named Barak (nicknamed “Birko”) gave me a menacing smile and said: “I told you months ago when I summoned you for questioning that I would soon come and snatch you from your bed and lock you in prison for a long time. And that I would do it with a smile on my face.”

And so it happened. The three judges of the District Court of Haifa fulfilled a promise they made to the Shin Bet. And when one of the judges was promoted to the Supreme Court, the Israeli media highlighted his “achievements” – which included my case, over which the chief judge presided and handed me a nine-year sentence.

Physical and mental torture

I would say that the first three weeks of my detention were the most difficult.

The torture I sustained in the interrogation rooms of the Shin Bet headquarters was not only physically scarring, but was also meant to break my spirit.

The Shin Bet refers to this stage of interrogation as “the vacuum”, a torture technique that aims to suck the souls out of prisoners’ bodies by subjecting them to physical pain so unbearable that it destroys them psychologically.

The conditions of confinement are equally considered torture under international law. The Shin Bet cells were too cramped and narrow for my body size and the walls were rough, with sharp protrusions, making it impossible to touch them let alone lean up against them. The bare walls, dim lighting and foetid odour all contributed to the mental torture.

The mattress was as putrid as the cell – thin and laying flat on the cold floor – with a blanket but no pillow, forcing me to rest my head on one of my shoes, which at least had a homely and familiar scent to it.

The air conditioner was constantly set to very low temperatures, making the moments when they transported me to the interrogation rooms – blindfolded and with my hands and feet shackled as I walked up a long staircase – the only times in which my body did not shiver from the harsh cold.

Meanwhile, in the interrogation room, they employed the “Shabeh” against me, a torture method that became known in the west as the “Palestinian chair” after American occupation forces infamously used it on Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib prison. I was forced to sit on a small child-sized chair, fixed to the floor of the room – facing the interrogator – with my hands and feet bound, incapable of any movement.

The agents took away the leather jacket I wore at the time of arrest, saying I was not allowed to dress in better clothes than what they were wearing. They use the freezing air as torture, blasting the air conditioner above my head and back, until I feel as if I am fading away or becoming numb. By then, my body and mind are breaking down together, leaving me with agonising pain.

Time is meaningless in the interrogation cells. There is no sunlight or darkness, no window and no key for the heavy metal gate, so the prisoner steals a tiny beam of light from the key slot. Day and night are meaningless underground. The light is constantly dimmed, by design.

While Israelis protest against Netanyahu and Ben-Gvir’s war on the judiciary, the high court of Israel enables the state’s use of torture against Palestinian prisoners.

READ: How Israel’s Supreme Court enables torture of Palestinian prisoners

No Christian ‘customers’

One day, I asked the prison guard for a book to read. After asking the investigators, he replied that no books are allowed except for holy books. So that is what I asked for. After consulting with the investigators again, he said there is only the Quran. I immediately asked for it.

He again left to ask for permission before returning and saying: “You are not Muslim, so you are not allowed to have the Quran.” Accordingly, I requested the Bible. The guard did his routine walk to the investigators, returning maybe half an hour later (as I lost all sense of time). He said: “There are no copies of the Bible. We don’t have Christian customers.”

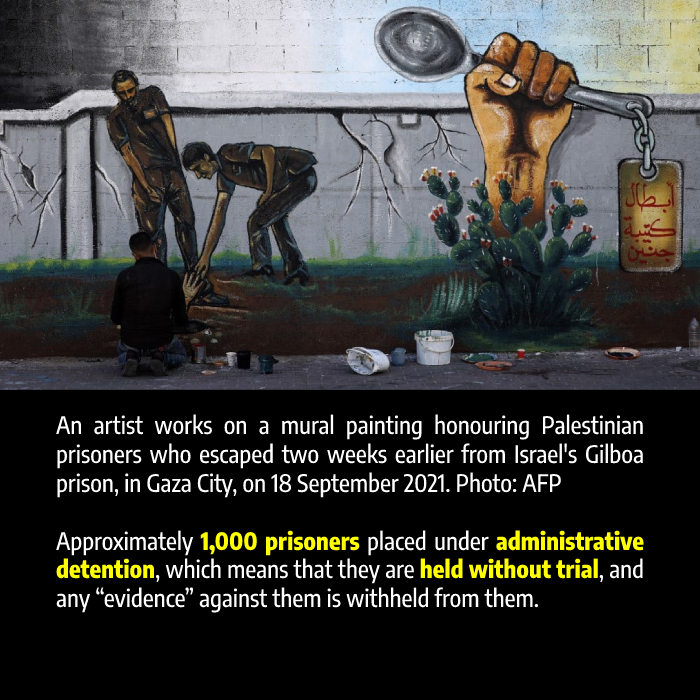

Twenty-two days later, I was transferred to the Israeli Gilboa prison, a maximum security prison in Bisan, a town located in the northeast of occupied Palestine.

Standard prison procedures meant an immediate and forced interrogation with the intelligence officer upon arrival. I was then given a prison jumpsuit, which wasn’t even my size.

I was placed in section one of the prison, which at the time was reserved for prisoners from Jerusalem and other areas of 1948 Palestine. Once I entered the unit and the gate closed behind me, all the prisoners rushed to greet me – embracing me one by one – a tradition among prisoners.

Moving from the Shin Bet solitary cells to general population prison felt like coming back home, although not the family one. With my fellow prisoners, I began to feel the need to create meaning for my individual and collective life in detention.

One time, in cell number nine, section one of Gilboa prison which was supervised by the prisoner Maher Younis – who was released in January of this year after 40 years of imprisonment – I volunteered to prepare lunch or dinner. While making mujadara, a lentil and rice dish I am good at, I chopped and fried all four onions I found in the cell. When I was done cooking, I was proud of myself and my meal, only to realise minutes later, to my horror, that I caused a food crisis by using up all the onions at once, which were supposed to last for another half a week for the eight prisoners in the block.

As the days passed, the Shin Bet guard’s words continued to haunt me. What did he mean by “we don’t have Christian customers”? Why didn’t he leave it at saying there is no Bible, rather than mentioning the lack of Christians? Nothing happens by chance with the Shin Bet.

The interrogators are trained to weaken the “customer”, in their words, by stressing that you are alone, there is no one with you, there is no one like you, you are a stranger to the prisoners because you are a Christian and so you will spend the prison term estranged from the other prisoners.

Caged holidays

A strange scene is captured during the holidays in prison: there are prisoners rejoicing in the yard surrounded by high walls, the Israeli flag in the centre, and a roof built of iron grills that cut the sky into small squares as though they were pieces of a puzzle needing assembly to complete the scene. Zooming out, the prisoners are celebrating the holidays in one big cage.

The Muslim holidays of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha are celebrated collectively, and preparations for them begin days before the date with the talent of making cakes from scratch out of what is available in the commissary – showing hospitality to all 120 prisoners in the unit – and cleaning the yard and scrubbing down the cells with soap and water.

The holiday would begin at 6am but by 7am it was already over. As a social event, the feast started with prisoners going out into the prison yard, shaking hands, embracing and offering wishes of liberation such as “next year at home”, “next Eid with your loved ones”, and “freedom is near”.

The barber would shave the head of all the prisoners a day or two before that, and each prisoner would wear his best outfit and any available or smuggled cologne – only if it is of high quality. Some of the old prisoners kept colognes for more than 10 years when it was still possible for their families to bring them.

Finally, once all the prisoners arrive at the yard, the Eid prayer and sermon would begin.

Meanwhile, the jailers observe, record and make sure that the sermon does not deviate from the text that the prisoners presented to the administration before – under the pretext of preventing incitement. Prisoners, however, pay no attention to the jailers. Following that, the prisoners come together in a big circle for the holiday greetings – shaking hands, embracing and congratulating each other.

Then it is time for refreshments prepared by the prisoners or purchased from the canteen, and thus the rituals come to an end. During this time, the prisoners are able to visit each other in the cells, and sometimes it is possible to organise visits between prisoners from the different units if the jailers permit. The political factions also organise delegations of their members to exchange visits and offer official holiday greetings.

When the visits are over, the prisoners return to the cells and the holiday comes to an end.

I would participate in the whole event by going to the yard and offering greetings. When I would pass by the prisoner Nader Sadaka, we would start laughing, as I am a Christian from Haifa and Nader is from a Jewish Samaritan sect from Nablus. He is serving a life sentence for his role in the Second Intifada.

When all prisoners gather, there is room for joy. But Christmas hits differently – no other prisoner celebrates Christmas but me. One day I wrote to my family: “Before prison, I would wish for the holiday to last for days, but here I wished it to pass as fast as the light or to not happen altogether.” Holidays are a time of happiness, but in prison, they would fill me with sadness.

I was the only Christian, though at times we were two, so the Christmas circle was meaningless. All I could think about on Christmas Eve was my family: my wife, Janan, and my two daughters, Hind and Huda.

I was wondering what each one was thinking: my wife’s feelings of loneliness, how they’d spend the holiday, and how I could tell them that they looked beautiful and dressed nicely.

I thought about how I wouldn’t be there to prepare Christmas dinner or breakfast the following morning – things I have mastered and loved doing. But most importantly how would I hug each one? None of this was possible except in my imagination. Nevertheless, I would remember the Shin Bet guard’s deliberate message of not having Christian “customers” so I decided to celebrate Christmas.

My origin is from the village of Al-Boqai’a in Western Galilee, an ancient village dating back a few thousand years. Its residents were mostly Druze, as well as Christians, Muslims, and Jews (Arab Jews) who considered themselves Palestinian.

The people of the village used to celebrate all holidays and visit each other during all of them. This familiarity and solidarity between people have deep roots in Palestine and the culture of its people.

For me, the Christmas tradition meant refraining from going out for early morning exercise, which I adopted throughout my prison term, and wearing the most elegant clothes – relatively speaking, as the prison forbids shirts, belts, thick jackets, blouses with hats and even interferes with shoes.

Contrary to Muslim holidays which were held collectively in the morning, at noon on Christmas Day and without prior notification, dozens of fellow prisoners from all Palestinian political factions would come to my cell (which fits about eight people), to convey holiday greetings with gifts they would purchase from the canteen and postcards with greetings, designed by the prisoner, the creative artist, Samer Miteb, from Jerusalem, who had been sentenced to 24 years.

Then, in the middle of the crowd, young men would start to raise the sound of Arabic songs from an old tape recorder with headphones invented by the prisoners, to make space for the singing and dancing floor, celebrating Christmas and celebrating me, lifting the spirit and bringing joy to the people.

One prisoner owned two smuggled candles that he held onto for 12 years. My friend Bashar Khateb lit the 12-year-old candles for a minute and then blew them out, saving them for another future joyful occasion.

‘We are all Palestinians’

In 2017, the Israel Prison Service dismantled what they called the section of Arabs of Jerusalem and the Palestinians of 1948, and I was transferred to the Nablus section. There is a story behind the naming of the sections and the distribution of prisoners.

Over the course of five decades, the prisoners were held in prisons without any geographical affiliations. Succeeding the Oslo Accords of 1993, the prisoners of Jerusalem and 1948 Palestine were separated into a section of their own.

Later on, after building the separation wall in the West Bank and surrounding cities with checkpoints, settlements and military bases, the occupation sought to create local and regional Palestinian identities at the expense of a unifying Palestinian identity.

As the West Bank formed one spatial and geographical continuity of Palestinians, throughout the first and second Intifadas, and the borders were relatively open to the Palestinians of 1948. Along the construction of the wall, Palestinians became isolated from each other.

A whole generation has grown up after the wall and all it saw in front of it was the wall and its narrow horizon. Seeking to engrave the wall in the minds of the young Palestinian generations, occupier Israel opted to create contradictory local identities, instead of one inclusive identity.

This is the case in the West Bank, Gaza, and 1948 Palestine, and this is the same in the prisons. Initially, the Prison Service separated the prisoners of Fatah and the PLO movement from prisoners affiliated with Hamas.

In an effort to further isolate incarcerated Palestinians, the Prison Service divided them by region: separate units for prisoners from Nablus, Jenin, Tulkarem, Bethlehem, Hebron, and so on. This division constituted a tool of control and hegemony by the occupier.

I told a fellow prisoner that we are from the same people, culture, affiliations, and the same Arab civilisation, so there are no differences between us

In the Nablus unit, my peers welcomed me warmly, as I them. There, I maintained my daily regimen of morning exercise, reading, and university education for the prisoners who were accepted to study in a special course provided by Al-Quds Open University, as well as preparing a number of them for the graduation exams approved by an academic committee of prisoners.

Also, due to my knowledge of the Hebrew language and the Israeli procedural system, I would help prisoners compose letters and complaints, and challenge their cases and other abuses. A plastic table outside became my “office” for such requests.

I never liked to be referred to by my sectarian or religious identity – we are all Palestinians after all. Yet, the prisoners created this identity for me in a positive, humane, and curious manner. Once, I was walking with a 42-year-old prisoner who had spent 22 of those years behind bars. He said to me: “No offence, but I have never spoken in my life to a Christian person. In Nablus, they have become few, and I live in a village on the outskirts of the city. So, excuse my question, but are your habits similar to our habits in terms of eating, socialising, joy and sadness?”

Honestly, I liked the question due to the sincerity of the asker. I told him that we are from the same people, the same culture, the same affiliations, and the same Arab civilisation intertwined with the Islamic civilisation, so there are no differences between us. He thanked me and started apologising, so I stopped him, and we then talked about how the occupation and the coloniser wants us to have clashing identities, not harmonious ones.

The prisoners used to call me al-Hajj Abu Hind, or al-Hajj Ameer, which is a common tradition in calling elderly prisoners. I kept pace with that and used to respond normally until the prisoner Salah al-Bukhari from Nablus noticed that, and alerted the prisoners that I was not a Muslim. He initiated everyone calling me “Father”, out of respect, as in the church tradition.

When I asked him not to repeat that, it was too late. The nickname had already spread and I no longer had control over it. He still jokes about it to this day inside prison, when calling me from smuggled phones – a reminder of the reality of life in an Israeli jail.

Source: Middle East Eye. 18 April 2023