By Peter Oborne in Nablus, occupied Palestine.

The life of a local journalist in Britain is comparatively simple. Weddings. Funerals. A spot of council corruption, and the local football team.

Less so in Nablus, though Nasser Ishtayeh has covered plenty of funerals.

The brutal circumstances of the occupation dictate that he’s a war photographer. Each job can be his last.

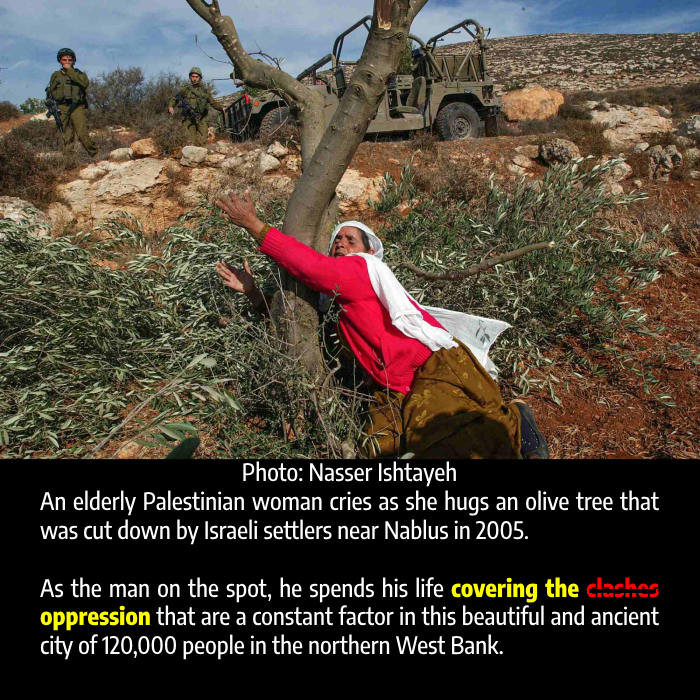

As the man on the spot, he spends his life covering the clashes that are a constant factor in this beautiful and ancient city of 120,000 people in the northern West Bank.

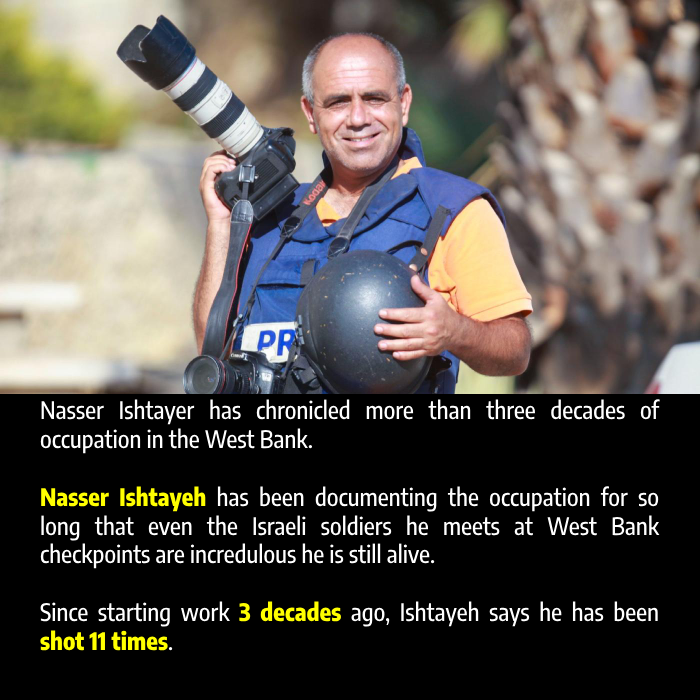

Since starting work three decades ago, Ishtayeh says he has been shot 11 times.

Eighteen months ago, he was taking photographs in a nearby village when a soldier fired at him from six metres.

There seemed to be no tension and he was not wearing a helmet. The rubber-tipped bullet grazed his skull, and he has the scar, a dull orange welt, to prove it.

The soldier aimed at his head, but at the last moment Nasser looked behind him at some children. He believes that backwards glance may have saved his life.

Ishtayeh says he did not bother to report the incident because he had complained dozens of times about other episodes, and nothing had ever been done.

“The blame always falls on the journalist,” he says.

Last month, both Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and the International Federation of Journalists condemned what both organisations described as “systematic” attacks on Palestinian journalists and a “culture of impunity” within Israeli security forces.

The most painful wound came, he says, when he was shot in the foot. Once, two rubber bullets struck him from behind.

“I had to sleep on my stomach for a month,” he recalls, “with an icepack on my arse.”

“If they want to attack journalists,” continues Ishtayeh, “they sometimes shoot at walls or at potholes so we get hit by the ricochet.”

Besides bullet wounds, Ishtayeh says he’s been jailed countless times, often had his camera smashed and frequently been assaulted by settlers.

In 2004, when then-prime minister Ariel Sharon ordered the removal of settlements near Nablus, settlers threw Ishtayeh down a well and left him for dead. He owed his life on this occasion to Israeli soldiers, who hauled him out and took him to hospital.

By then he was in a coma and widely reported to be dead.

When he meets soldiers they ask him: “You still alive?” In return he berates them at checkpoints.

Iconic images of occupation

When we met for dinner at a Nablus restaurant, he’d come straight from covering a settler incursion in the village of Turmusaya, 15km south of Nablus.

“Thirty houses were burnt. Sixty cars destroyed. The IDF was protecting the settlers.”

One man, Omar Hisham Jibra, was fatally shot by the settlers. Many residents of the village have close links to the United States and Jibra’s wife and children were American citizens.

Ishtayeh says that even though he and media colleagues had all been carrying press accreditation, the settlers attacked them as well.

“I had to flee.”

But not before he’d got the pictures he needed.

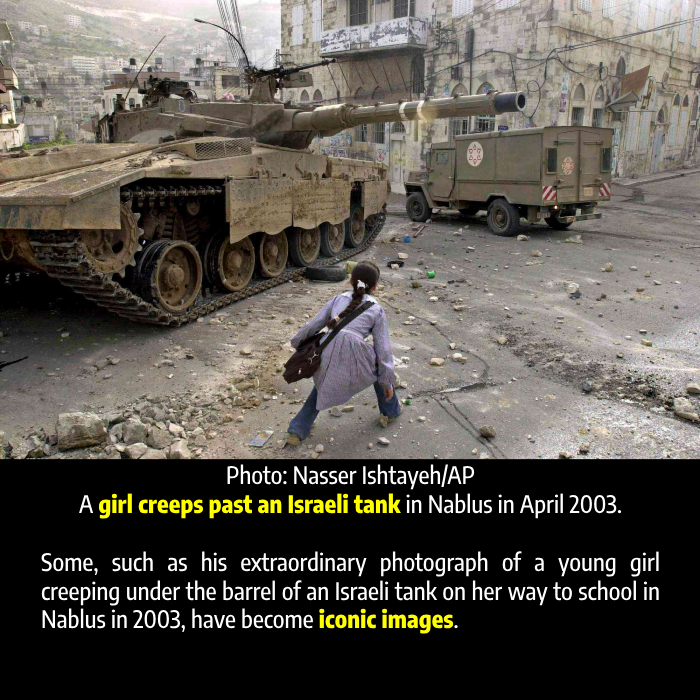

Ishtayeh’s work has made him one of the most respected war photographers in the world. Many of his pictures have been across the front pages of the world press.

Some, such as his extraordinary photograph of a young girl creeping under the barrel of an Israeli tank on her way to school in Nablus in 2003, have become iconic images.

In his remarkable career, which included 25 years at the Associated Press news agency, he’s chronicled more than three decades of Israeli occupation.

Now freelance, Ishtayeh, 51, looks older than his years. He’s a small man with a weathered face and an engaging smile.

Local reporters confirm that Ishtayeh is often cheerful.

But he says that when he sleeps he is tormented by nightmares: “All the time I am dreaming that a soldier is going to shoot me.”

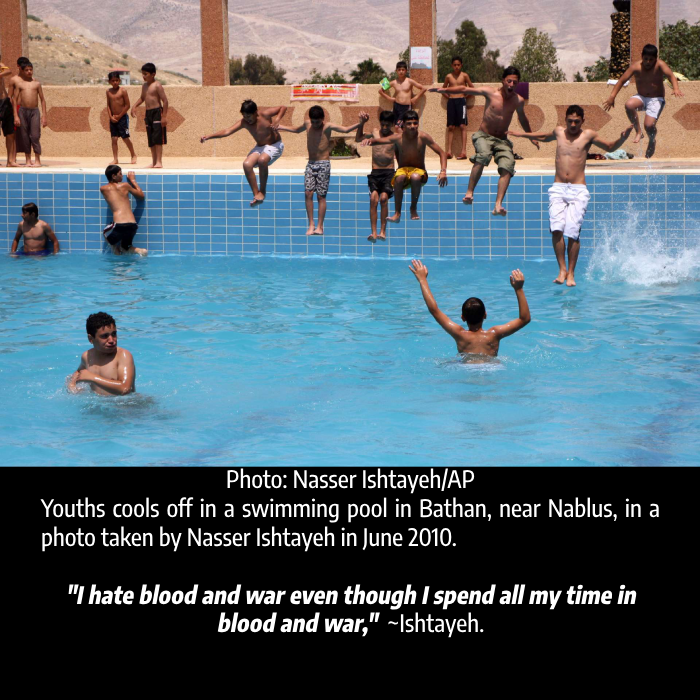

At such moments, he says, “I think of making photographs of everyday life”.

Life, and Death

There is little chance of that today, with Israeli security forces in recent weeks carrying out a succession of brutal raids in the West Bank, and settler attacks against Palestinians also on the rise.

Ishtayeh brought his 17-year-old son Mohammad with him to dinner. I ask the boy what he feels about his father’s job.

“It’s very worrying,” comes the reply. Mohammad shrugs his shoulders. “But it’s what he does.”

The intelligent young man has no intention of following his father into photojournalism, and hopes to study medicine at university, following in the footsteps of his two elder sisters.

The next day, Ishtayeh tells me, he will take a rare day off and collect his 19-year-old daughter Dana from Jericho. She’s coming back on holiday from her university work in Cairo.

There is a third sister, Donia, who Mohammad has never met.

Donia, whose name in Arabic means “Life”, was three months old when killed by the Israelis in Nablus, at the height of the Second Intifada when air strikes were pounding the city.

Ishtayeh recalls that she died during an Israeli operation called “Defensive Wall”.

She was in an ambulance travelling to hospital when the vehicle was struck by a tear gas grenade. “She was killed by the gas,” he states sombrely.

True to form, he took out his camera and photographed her final moments.

The ambulance was just three minutes from the hospital, but the soldiers had declared a closed zone and did not allow the vehicle to enter.

Yasser Arafat, then president of the Palestinian Authority, would hold up a photo of the dead baby at the United Nations.

Many of Ishtayeh’s best friends have been killed. I asked him to name some of them.

83 Palestinian reporters have reportedly been killed by Israeli forces since 1972.

READ: Shireen Abu Akleh killing: Israel’s record of killing Palestinian journalists

Tarek Ayoub and Mazen Dana, both killed in Iraq. He adds Nazeeh Darwazeh, shot in the head by Israeli soldiers during the Second Intifada in Nablus, and Shireen Abu Akleh, killed by an Israeli sniper in Jenin last year.

He says he was one of the last people to speak to Abu Akleh before her death. She rang him as he drove from Nablus to join her in Jenin camp.

For four years they had covered the Second Intifada from Nablus, staying in the same hotel in those desperate times. “She worked in all of Palestine, in every province, city and village. Everyone loved her.”

Does he have Israeli friends? His face lights up. “Yes. We have many meetings. Before 2000 they used to visit me at home in Nablus and I would travel to meet them in Al Quds [Jerusalem]. They always say how sorry they are when I am injured.”

He says three episodes have affected him most in his career.

First, the death of his daughter Donia.

Second, an Israeli attack on a conference in Nablus more than 20 years ago which left seven people dead.

He was on the way to cover the event when he met a friend asked him to meet for a coffee. “A cup of coffee rescued me from death.”

Third, the Israeli assassination of Abu Ali Mustafa, the Palestinian militant leader killed in 2001. Mustafa was the first person Ishtayeh interviewed as a young journalist.

I ask him what advice he has for photographers wanting to follow in his footsteps. He says: “Do not move to hot spots unless you know what’s going on. Wear your helmet and vest. Put the press sticker on your car.”

Colleagues say that he is generous to aspiring war photographers, allowing them to accompany him as he works, helping them to learn their trade.

“I hate blood and war even though I spend all my time in blood and war,” broods Ishtayeh. “But I selected this career to convey the painful truth of the occupation to all people, other nations and even to the people of Israel themselves.”

The day after our interview we both attended a graduation ceremony for journalists at the Tanweer Centre in Nablus. But Ishtayeh was called away when news came through that Israeli forces were attacking the nearby refugee camp in Balata.

As I emerged from the ceremony an hour later, the loudspeakers of the local mosques were announcing: “There’s a martyr at Balata.”

As ever, Nasser Ishtayeh was on hand to record the latest death in the never-ending occupation.

Additional reporting by Fateen Obaid.

Source: Middle East Eye. 17 July 2023